Leh, the capital with 25 thousand people, is the only town of any size in Ladakh. Still no traffic lights though!

Heading west from Leh on the road to Kashmir, we follow the Indus river. The Indus river, from where India gets its name, originates in Southern Tibet, from the slopes of the great and sacred Mount Kailash.

The snows of Mount Kailash give rise to 4 great rivers that traverse epic journeys of thousands of kilometres over the plateaus of Tibet, through the Himalayan mountains and the plains of the Indian subcontinent, sustaining the lives of a Billion people along the way.

Heading west from Leh on the road to Kashmir, we follow the Indus river. The Indus river, from where India gets its name, originates in Southern Tibet, from the slopes of the great and sacred Mount Kailash.

The snows of Mount Kailash give rise to 4 great rivers that traverse epic journeys of thousands of kilometres over the plateaus of Tibet, through the Himalayan mountains and the plains of the Indian subcontinent, sustaining the lives of a Billion people along the way.

The Indus flows north – known as Sengge Khabab to Tibetans (River originating from the Lion’s mouth)

The Satluj flows west – known as Langchen Khabab to Tibetans (River originating from the Elephant’s mouth)

The Karnali flows south – known as Mapcha Khabab to Tibetans (River originating from the Peacock’s mouth)

The Brahmaputra flows east – known as Tachok Khabab to Tibetans (River originating from the Horse’s mouth)

The Satluj flows west – known as Langchen Khabab to Tibetans (River originating from the Elephant’s mouth)

The Karnali flows south – known as Mapcha Khabab to Tibetans (River originating from the Peacock’s mouth)

The Brahmaputra flows east – known as Tachok Khabab to Tibetans (River originating from the Horse’s mouth)

As we near Kargil, my thoughts turn to a less spiritual reality of these mountains. In 1999, India and Pakistan fought a bloody war on the mountains around Kargil resulting in thousands of soliders dying on both sides. After Pakistani incursions into Indian territory, the Indian army fought heroically to regain lost mountains. Many individual stories of courage and sacrifice emerged from the war and have inspired a new generation of patriots across the country. Jigmet told me about the role of the Ladakh Scouts, an Infantry regiment of the Indian Army specialising in mountain warfare. This regiment, consisting of Ladakhi and Tibetan Khampa warriors (the same people who fought the Chinese when they invaded Tibet), contributed greatly towards the Indian Army winning the Kargil War and has been much decorated in their short history. Local Ladakhi man, Colonel Sonam Wangchuk, who received one of the highest Military honours for his bravery during the Kargil war, has become a source of pride and inspiration for all Ladakhis and in every village we visited, at least one person claimed to be related to Colonel Wangchuk.

It took us 3 days driving from Leh to get to Padum, the centre of Zanskar. Passing along the way, exotic scenery such as the Noon-Koon Mountain peaks (7800M) and the Drang Drung glacier, which is literally a river of ice.

Drang Drung Glacier

Drang Drung Glacier

On reaching Zanskar, we based ourselves in Karsha Gompa (Monastery). The team organised a nature orientation course for the local school kids while I roamed around aimlessly smiling at everyone and entertaining the kids. Then one day the director said "Action" and we headed for Bardan Gompa, which is where the road (for lack of a better word) ends. It’s all walking from here on.

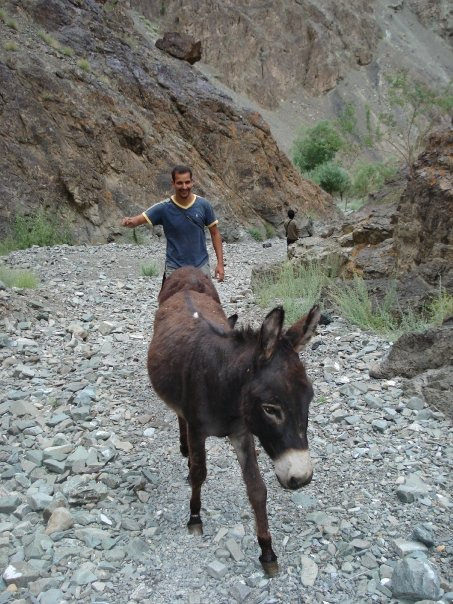

Strapping on our backpacks, 4 of us (Jigmet the leader, Angmo – a young, hardy Ladakhi girl, Sonam – a free spirited, squint-eyed young Ladakhi boy and myself) started walking up the Lungnak valley. The Lungnak valley goes up the Tsarap-Lingti river in a south easterly direction all the way to its source on the glaciers of the 5200M Shingo La Pass.

The first day was hard. I’d done heaps of mountain trekking in the years gone by but years of sitting in an office, hunched over a computer had taken its toll so my 20KG backpack ate into my shoulders while the steep terrain strained my thighs till they wobbled. I walked, gasping in the thin air (our trek started at 3900M and went uphill till 5000M, climbing and descending over a thousand vertical metres in a day) and tried to not shame my ancestors in front of these hardy mountain people

But the first day is always the hardest on any expedition and soon my body got used to it, my confidence rose and I was keeping pace with my companions easily.

The scenery was spectacular as we gained height, crested gorges and forded rivers. On our 3rd day, we saw a few Bharal (wild Blue sheep) and where there is Bharal, there is the possibility of Snow Leopards! Though Jigmet had made it pretty clear that we were unlikely to see a Snow Leopard on this trip since it was only August yet and the leopards wouldn’t start descending from the heights till after the first snowfall in October (he was right of course, we never did end up seeing a snow leopard though that never took anything away from the experience). But being a tracker, Jigmet couldn’t help tracking the Bharal. His senses immediately heightened and he was like a wild animal tracking his prey. He looked under rock overhangs and pointed out scratches that a Snow Leopard had made to mark its territory, though they weren’t recent. Snow Leopards are incredibly territorial and since prey is hard to hunt in this steep and unforgiving terrain, a single Snow Leopard may patrol 500 square kilometres. Snow Leopards are also nomadic and don’t typically have a “home base”, which adds to the difficulty in reliably tracking them. An expert tracker will look for signs in the terrain to determine if a snow leopard may be in the vicinity.

We walked every day through incredible mountain scenery and stopped at night, usually in a village where someone would offer us a bed to sleep. The best nights were the ones we spent sleeping under the stars on rooftops or in the wild. The night sky was so clear, it felt like you could touch the milky way. And because the air is so dry, there is no dew to worry about in the morning. Jigmet knew someone in every village along the way and sometimes I wondered if he might be more well-known than Colonel Sonam Wangchuk, the war hero. Some evenings we would get the village together and hold a consultation session to understand their views and concerns regarding the Snow Leopard.

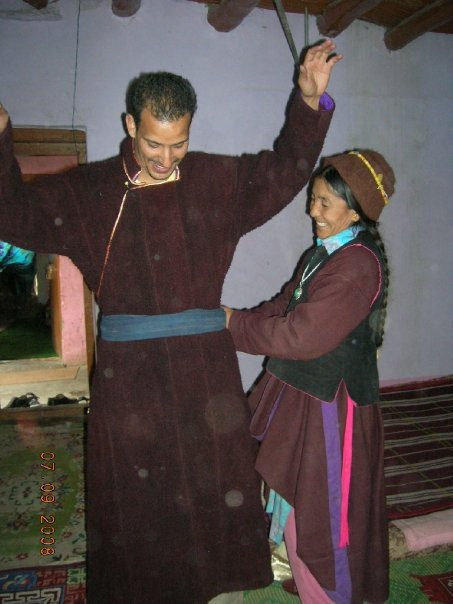

These were invariably polite and pleasant discussions and usually ended with the drinking of “Chhang”, home-made barley beer. It is an acquired taste and reeks horribly but it does the job and you even get used to it after a couple of weeks. Even their tea is unusual and consists of dollops of salted yak butter mixed in with the tea. It’s all designed to keep them warm and hydrated in the cold and dry climate but it takes a bit of getting used to. I was a bit of a novelty for most villagers as few outsiders ever visit this remote area, and most just walk through without stopping in the villages. I thoroughly enjoyed my interactions with these simple people and wished I knew more of the language to have richer conversations. But smiles, sign language and my spartan Tibetan got me through most of it. There was the odd hilarious moment like when an elderly lady pointed at me and motioned for me to take my clothes off. I thought, shit, the oldest profession in the world is well and truly alive even in this remote corner of the world! But seeing my shocked expression, Jigmet quickly interpreted the lady’s innocent question about whether I wanted to wear the traditional Ladakhi robe (called Goncha. The Tibetan version, which is very similar, is called Chuba).

One morning Jigmet informed me that today’s going to be a very special day. I asked him why but he just smiled and said “You’ll see”. Mid-afternoon I turned a corner in the trail and I saw. And my jaw dropped.

Phugtal is a remote monastery, carved into a cliff, tucked away in the folds of Zanskar. From far it looks like you’ve stumbled onto the BatCave! As you get closer, you start to see the scale of human construction, which is dwarfed by the size of the mountains surrounding it. It is a vast complex yet so in tune with nature’s contours. We visited the incredible monastery and met a few monks, who retreat to Phugtal for periods of isolation and meditation. It was a serious place but there were pockets of mischief. Or maybe I was the pocket of mischief.

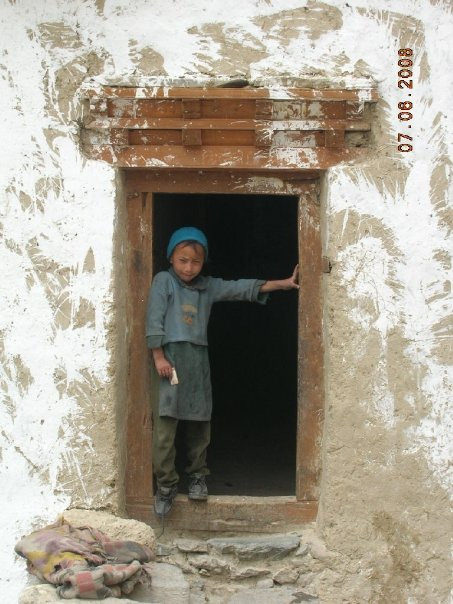

We camped in the village of Yugar across the river from Phugtal. The village was 4 houses packed tightly together surrounded by green fields of nascent Barley. There was a particularly cheeky little girl who came around in the morning to harass us. She stealthily followed me as I went to the fields to take a shit and laughed all the way back to the village when she saw me take my pants off!

I had a great time playing hide and seek with her and the other kids. A little pixie she was. A little pixie with great spirit. I wonder how she’s doing and what became of her.

I had a great time playing hide and seek with her and the other kids. A little pixie she was. A little pixie with great spirit. I wonder how she’s doing and what became of her.

From here the trail forks, one goes east towards Tibet and the other goes south towards Shingo La pass and onto the rest of India. We went south towards the pass, gaining height till we reached the isolated and spectacularly located settlement of Kargyakh. After spending the night here, we turned around and headed back down the valley, retracting our steps.

In another week we were back in Padum, meeting with bureaucracy, trying to secure government funding for our projects. I was really starting to feel like part of the SLC team and had gained their trust and respect. It was a great honour and hugely satisfying.

After recuperating at basecamp for a few days, we headed down the Zanskar river to Zangla, the historical capital of Zanskar. It’s now just a village with a hundred people but its location, at the entrance to the fearsome Zanskar gorge, betrays it as a seat of power. An evening walk to the ruined Zangla fort on a mountain top above the village was one of the highlights of my entire stay in Ladakh. The setting sun set ablaze mountain tops with deep, rich hues while the valleys cast eerie shadows, the wind carried the call of howling wolves and giant Golden Eagles went shopping for dinner in nature’s supermarket in the skies. The 4 of us played hide n seek amongst the ruins and then raced each other slipping and sliding down the mountain.

We had a party that night in a friend’s house. Much Chhang was drunk and I stunned a few people with my wild Bollywood dancing moves. I’m told my pelvic thrusts were the talk of the valley for days after.

Soon after this, our time in Zanskar came to an end. We offered our thanks and prayers in Bardan Gompa and headed north, towards the Pakistani border.

We were heading to Jigmet’s village, Skyurbuchan, along the Indus river. Along the way, we diverted through an area called Dah-Hanu, where the inhabitants claim to be of pure Aryan ancestry descendent from the time of Alexander the Great, when he invaded India over 2 thousand years ago.

We were heading to Jigmet’s village, Skyurbuchan, along the Indus river. Along the way, we diverted through an area called Dah-Hanu, where the inhabitants claim to be of pure Aryan ancestry descendent from the time of Alexander the Great, when he invaded India over 2 thousand years ago.

Whether that is true or not who knows but the people certainly look Germanic, many have blue eyes and apparently there’s blondes around too. They also have unique dresses, customs and religious beliefs that are distinct from the Buddhists of Ladakh. Very few people are allowed to visit here as its a politically and culturally sensitive area and you need a special permit but we sailed through all the check points since Jigmet’s village, Skyurbuchan, is in this area.

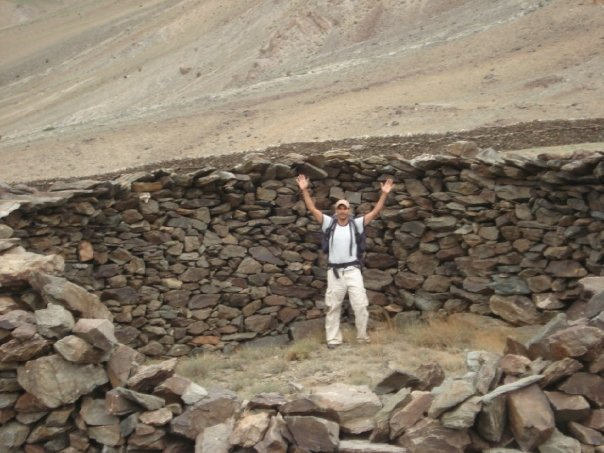

At Jigmet’s village, we finally relaxed in the comfort of home. His mother plied us with food while his dad brewed vast vats of Chhang! It wasn’t all fun and games though, I got involved in the village life and pulled my weight and sometimes pulled more than that!

We walked around the mountains every day and visited the “upper village”. Typically, in Ladakh, there is a main village in the valley and a collection of huts further up the mountains, which is used in summers as a base for grazing animals. Sheep, Yak and Dzo (cross between a cow and a yak) are left to roam the mountains and counted and collected every few days.

After an idyllic few days in Skyurbuchan, we returned to Leh and set about writing our reports and planning the implementation of the project. I spent my days in the little office writing a report and strategy paper on the Homestay project and whiled away my evenings roaming the bazaars and drinking beer in the rooftop restaurants with backpackers and old mates. One day I borrowed a Royal Enfield from a mate and did a quick run up to the highest mountain road in the world (at the time), Khardung La (5600M). Just because it was there. The bike wheezed and puffed in the thin air but got me up and back down the mountain without missing a beat.

One of my old mates, Nyima, is a ladakhi river rafting adventure guide who runs white water rafting and kayaking trips all over Ladakh. With his help I took my whole SLC team out rafting on the Zanskar river. The Zanskar is a wild and unforgiving river with water temperature just above freezing, many class 4 rapids and no habitation or support in case of accidents. None of the SLC folks had ever done white water rafting before and none of them knew how to swim. For once I enjoyed seeing them out of their comfort zone while I was totally at home! We only rafted a small section of the river but the 10 day Zanskar River run is one of the greatest river adventures to be had on the planet.

It was now late autumn and getting seriously cold. Soon it was time for me to head to Delhi and pull the curtain down on this most amazing adventure.

I saw lots of wildlife; Marmots, Wolves, Blue Sheep, Ibex, Eagles but we never did see a Snow Leopard in all this time wandering the mountains of Ladakh. We saw shit. No really, we saw leopard shit, we saw leopard tracks, we saw leopard markings, we even saw the carcass of a Blue sheep killed by a Snow Leopard. But to be honest, I almost felt relieved that we didn’t see one. The Snow Leopard is a mythical beast for me, a symbol of wild earth and all that is still primeval in this world. And I am happy in the knowledge that there are still secrets out there. There are still things and places hidden from Google and till the last Snow Leopard is photographed, tracked, trapped, radio collared and neutered, there is hope for the wild things amongst us.

I saw lots of wildlife; Marmots, Wolves, Blue Sheep, Ibex, Eagles but we never did see a Snow Leopard in all this time wandering the mountains of Ladakh. We saw shit. No really, we saw leopard shit, we saw leopard tracks, we saw leopard markings, we even saw the carcass of a Blue sheep killed by a Snow Leopard. But to be honest, I almost felt relieved that we didn’t see one. The Snow Leopard is a mythical beast for me, a symbol of wild earth and all that is still primeval in this world. And I am happy in the knowledge that there are still secrets out there. There are still things and places hidden from Google and till the last Snow Leopard is photographed, tracked, trapped, radio collared and neutered, there is hope for the wild things amongst us.

| Comments |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed